Steinhart Aquarium turns 100

Photos courtesy of California Academy of Sciences/Story by Dave Boitano

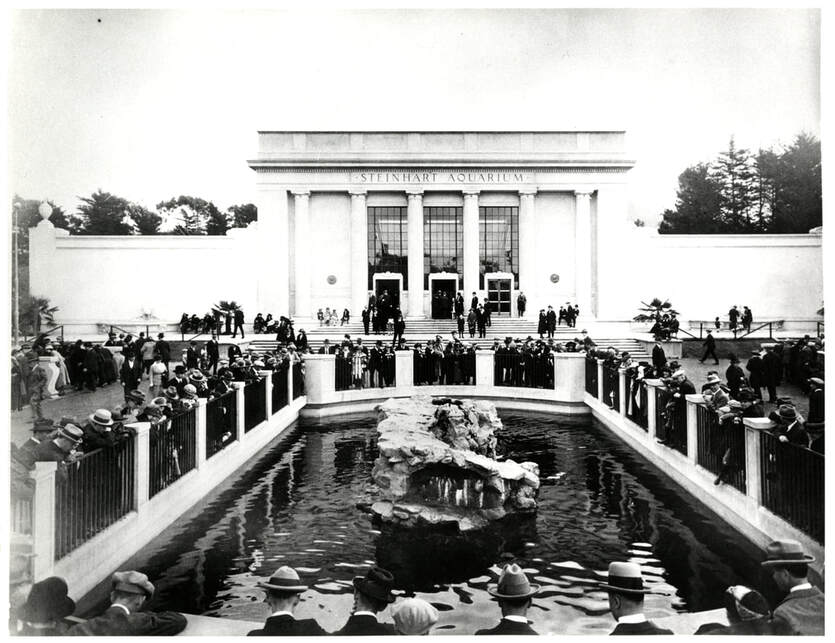

Visitors gather at the opening of the new Steinhart Aquarium in September, 1920

I was eight years old when I first visited Steinhart Aquarium. After an hour in the building, I was hooked.

I saw live alligators in an artificial swamp complete with a waterfall, large Amazonian fish swimming in huge tanks and venomous snakes resting in their terrariums, waiting for a chance to strike anyone foolish enough to put their hands in the tank.

I’ve been back to Steinhart more times than I can remember over the years and it never loses its allure.

And I’m not alone.

Over the past century, thousands of visitors have wondered at the exhibits in the aquarium and doubtless many more will during the next 100 years.

On this 100th anniversary, it’s time to take a fond look at all the unique people, creatures and trends that made Steinhart such an unforgettable attraction in a city known for its unique culture.

The aquarium opened on Sept. 29, 1923. It was the gift of two brothers, Ignatz and Sigmund Steinhart, who made considerable money during the city’s Post-Gold Rush era. Ignatz was a banker, and Sigmund a stockbroker

They wanted San Francisco to have a grand aquarium in the European tradition and Sigmund’s will set aside $200,000 for the project.

Ignatz insisted that the aquarium be in Golden Gate Park, run by the California Academy of Sciences, and maintained by the city.

It was the largest building in the academy complex, which had moved to the park after its downtown building was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire.

The building was renovated in 1963, and completely redesigned after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Over the years, Steinhart has housed more than its share of unique animals.

In 1939, an Australian Lungfish arrived on a Matson Lines ship and took up residence. That creature, named Methuselah, is still on exhibit today as the oldest living aquarium fish in the world.

In 1955, a biologist purchased a dugong, a manatee-like aquatic mammal and brought it to Steinhart. The animal was on display for only a month but became an instant media star.

“It became a national sensation,” said current Steinhart Director Bart Shepherd, “It was covered in Time Magazine, Life magazine and in the newsreels they showed before movies.”

Marine mammals have always been a major aquarium attraction. Over the years, Steinhart has housed “Butterball” the manatee, a pair of blind South American river dolphins and other Pacific dolphins in a 63,000 gallon tank. They were sent to Sea World in San Antonio, Texas in 1996 and the aquarium does not show marine mammals any longer.

Steinhart’s story involves its animals, but its history was ultimately shaped by the organization’s many directors.

None more so than Earl Herald, a Stanford University ichthyologist who arrived in 1948.

Herald was, according to Shepherd, “a force of nature” who had his share of supporters and critics.

“There were two opinions, you either loved the man and respected him or you didn’t,” he said.

The post-war era was a critical time for the aquarium, as scientists collected fish from throughout the Pacific Ocean and brought them back.

“At the time everything was new,” Shepherd said. “Television was new, airplane transit was new. We had just gone through the Pacific during World War II and there were all these islands with all these fish that nobody had ever seen before. And so they had the opportunity to bring these animals in.”

Herald put Steinhart on the map, Shepherd said, by creating “Science in action” a weekly television show distributed to local stations and syndicated nationwide.

The show (see below) was a kind of broadcast lecture in which Harold would acquaint audiences with the aquarium and the characteristics of marine creatures.

My favorite section was “Animal of the week” which featured snakes, lizards and other live critters handled with care by Harold and his assistants.

“Earl was good at doing that,” Shepherd said. “Getting Steinhart into the public awareness as a noted aquarium.”

Herald died while scuba diving in Mexico in 1973. His replacement was John McCosker, from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego.

Though McCosker had done research on eels, he was best known for his knowledge of sharks, including the ferocious Great White Shark.

McCosker brought Steinhart another first by capturing a Great White and displaying her in the Aquarium’s first roundabout, a circular tank where pelagic fish swam within a strong artificial current.

A crowd of 40,000 visitors over three days jammed the aquarium to see the predator. But the shark, nicknamed “Sandy,” couldn’t function within the tank due to a kind of sensitivity overload. Despite the accomplishment of bringing the first shark of this kind into captivity, McCosker decided she had to be returned to her ocean home.

“John realized it wouldn’t survive and realized he had done what he had set out to do, Shepherd said, “He wanted to release her. He wanted her to live.”

Outraged residents sent McCosker hate mail for sending an ocean predator back into the sea. Much of the hysteria was caused by the action-horror film “Jaws.”

“The public perception of a shark is that it kills you in the water,” Shepherd said.

“It doesn’t serve any useful purpose. It’s a man eater. It was a very different time.”

If the old aquarium was known for its traditional charm, the new Steinhart educates visitors about the aquatic world by taking visitors into imaginative environments.

A corridor full of tanks has been replaced with a living coral reef, a north pacific enclosure full of rockfish and a swamp occupied by a single albino alligator.

The snakes and other tropical animals haven’t left. They are now in a living rainforest where visitors climb toward the upper canopy and take an elevator down into a tank where they are surrounded by giant Amazonian fish.

It may not be the biggest aquarium in the nation, but Steinhart has the most diverse collection of sea life, Shepherd says.

In keeping with the tradition of Steinhart directors being researchers, Shepherd serves on the academy’s dive team and has explored deep reefs as part of an initiative called “Hope for Reefs.”

And like his predecessors, Shepherd will carry on Steinhart’s tradition of educating the public.

“The ability to connect folks with a living animal and the people who are studying it is so powerful,” he said.

I saw live alligators in an artificial swamp complete with a waterfall, large Amazonian fish swimming in huge tanks and venomous snakes resting in their terrariums, waiting for a chance to strike anyone foolish enough to put their hands in the tank.

I’ve been back to Steinhart more times than I can remember over the years and it never loses its allure.

And I’m not alone.

Over the past century, thousands of visitors have wondered at the exhibits in the aquarium and doubtless many more will during the next 100 years.

On this 100th anniversary, it’s time to take a fond look at all the unique people, creatures and trends that made Steinhart such an unforgettable attraction in a city known for its unique culture.

The aquarium opened on Sept. 29, 1923. It was the gift of two brothers, Ignatz and Sigmund Steinhart, who made considerable money during the city’s Post-Gold Rush era. Ignatz was a banker, and Sigmund a stockbroker

They wanted San Francisco to have a grand aquarium in the European tradition and Sigmund’s will set aside $200,000 for the project.

Ignatz insisted that the aquarium be in Golden Gate Park, run by the California Academy of Sciences, and maintained by the city.

It was the largest building in the academy complex, which had moved to the park after its downtown building was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire.

The building was renovated in 1963, and completely redesigned after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Over the years, Steinhart has housed more than its share of unique animals.

In 1939, an Australian Lungfish arrived on a Matson Lines ship and took up residence. That creature, named Methuselah, is still on exhibit today as the oldest living aquarium fish in the world.

In 1955, a biologist purchased a dugong, a manatee-like aquatic mammal and brought it to Steinhart. The animal was on display for only a month but became an instant media star.

“It became a national sensation,” said current Steinhart Director Bart Shepherd, “It was covered in Time Magazine, Life magazine and in the newsreels they showed before movies.”

Marine mammals have always been a major aquarium attraction. Over the years, Steinhart has housed “Butterball” the manatee, a pair of blind South American river dolphins and other Pacific dolphins in a 63,000 gallon tank. They were sent to Sea World in San Antonio, Texas in 1996 and the aquarium does not show marine mammals any longer.

Steinhart’s story involves its animals, but its history was ultimately shaped by the organization’s many directors.

None more so than Earl Herald, a Stanford University ichthyologist who arrived in 1948.

Herald was, according to Shepherd, “a force of nature” who had his share of supporters and critics.

“There were two opinions, you either loved the man and respected him or you didn’t,” he said.

The post-war era was a critical time for the aquarium, as scientists collected fish from throughout the Pacific Ocean and brought them back.

“At the time everything was new,” Shepherd said. “Television was new, airplane transit was new. We had just gone through the Pacific during World War II and there were all these islands with all these fish that nobody had ever seen before. And so they had the opportunity to bring these animals in.”

Herald put Steinhart on the map, Shepherd said, by creating “Science in action” a weekly television show distributed to local stations and syndicated nationwide.

The show (see below) was a kind of broadcast lecture in which Harold would acquaint audiences with the aquarium and the characteristics of marine creatures.

My favorite section was “Animal of the week” which featured snakes, lizards and other live critters handled with care by Harold and his assistants.

“Earl was good at doing that,” Shepherd said. “Getting Steinhart into the public awareness as a noted aquarium.”

Herald died while scuba diving in Mexico in 1973. His replacement was John McCosker, from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego.

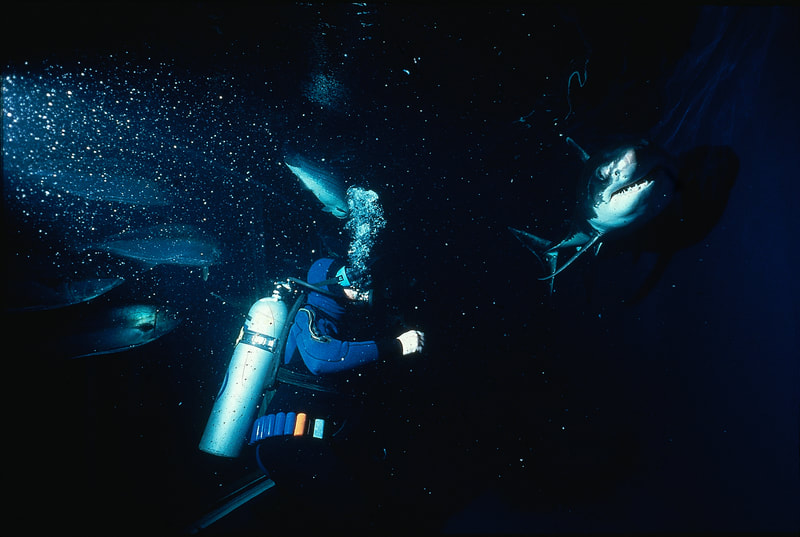

Though McCosker had done research on eels, he was best known for his knowledge of sharks, including the ferocious Great White Shark.

McCosker brought Steinhart another first by capturing a Great White and displaying her in the Aquarium’s first roundabout, a circular tank where pelagic fish swam within a strong artificial current.

A crowd of 40,000 visitors over three days jammed the aquarium to see the predator. But the shark, nicknamed “Sandy,” couldn’t function within the tank due to a kind of sensitivity overload. Despite the accomplishment of bringing the first shark of this kind into captivity, McCosker decided she had to be returned to her ocean home.

“John realized it wouldn’t survive and realized he had done what he had set out to do, Shepherd said, “He wanted to release her. He wanted her to live.”

Outraged residents sent McCosker hate mail for sending an ocean predator back into the sea. Much of the hysteria was caused by the action-horror film “Jaws.”

“The public perception of a shark is that it kills you in the water,” Shepherd said.

“It doesn’t serve any useful purpose. It’s a man eater. It was a very different time.”

If the old aquarium was known for its traditional charm, the new Steinhart educates visitors about the aquatic world by taking visitors into imaginative environments.

A corridor full of tanks has been replaced with a living coral reef, a north pacific enclosure full of rockfish and a swamp occupied by a single albino alligator.

The snakes and other tropical animals haven’t left. They are now in a living rainforest where visitors climb toward the upper canopy and take an elevator down into a tank where they are surrounded by giant Amazonian fish.

It may not be the biggest aquarium in the nation, but Steinhart has the most diverse collection of sea life, Shepherd says.

In keeping with the tradition of Steinhart directors being researchers, Shepherd serves on the academy’s dive team and has explored deep reefs as part of an initiative called “Hope for Reefs.”

And like his predecessors, Shepherd will carry on Steinhart’s tradition of educating the public.

“The ability to connect folks with a living animal and the people who are studying it is so powerful,” he said.

A century of aquarium innovation

Steinhart is the oldest continually operating aquarium in the nation. Scientists and staff have made history with a number of unique exhibits and activities during the past 100 years. They:

- Created the first live TV show to be filmed in an aquarium. Science in Action was hosted weekly by Steinhart Superintendent Earl Herald from 1952 to 1966,

- Displayed the first dugong ever cared for in a public aquarium (1955)

- Developed the use of copper sulfate to treat marine parasites (1955)

- Performed the first aquarium studies of susu, a blind river dolphin from the Ganges (1969)

- Bred a bushmaster (a highly venomous snake), which won the prestigious Bean Award from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (1969)

- Displayed bioluminescent flashlight fishes (1975)

- Displayed a great white shark for four days before returning her to the sea. (1980)

- Collected and displayed living corals and reef sharks together (1988)

- Captured and bred Burmese vine snakes (2001)

- Collected and displayed a coconut octopus.(2011)

- Hatched and raised ostriches in an indoor museum environment (2012)

- Used iPads as digital interactive graphics (2012)

- Got corals to spawn in human care (2018)

- Developed a patented submersible fish decompression chamber that makes it possible to safely bring fishes from deep reefs to the surface. (2022).

Directing and diving

Current Steinhart Director Bart Shepherd, left, is also a member of the academy's dive team, right, exploring deep reefs.

Shark comes to Steinhart

Former Steinhart Aquarium Director John McCosker, left, kept a female Great White Shark in captivity, right, for four days before releasing her.

Aquarium has seen changes during its history

Prior to its remodeling after the Loma Prieta earthquake, Steinhart featured an artificial swamp, left, and a fish roundabout, center. A living coral reef, right, is a key exhibit of the new aquarium.