Penguin family gets bigger

Fyn, an African penguin hatched in August of 2023.

Photo courtesy of the California Academy of Sciences

Photo courtesy of the California Academy of Sciences

March 20, 2024

African penguins are endangered in the wild, but at the California Academy of Sciences they are thriving. The colony of 20 birds has been busy increasing their numbers at a pace that has academy biologists happier than a penguin presented with a huge plate of herring.

Ten chicks have hatched in the academy’s penguin exhibit over the past 14 months ending in January. That might not seem like a lot, but, by comparison, it took a decade to breed the same amount of baby birds previously.

“Our colony is relatively small,” said Brenda Melton, Director of Animal Care and Wellbeing at the Steinhart Aquarium. “While the number of chicks may be common in a larger colony, for us it’s quite a feat.”

Melton serves on the steering committee of an organization of zoos and aquariums which plans the breeding of African penguins, based on maintaining healthy colonies.

Genetic diversity among the birds is crucial if the colonies are to remain healthy and avoid problems based on limited breeding stock. Birds can then remain where they were hatched or be transferred to another facility to bolster other colonies.

In the wild, penguins choose a mate, build a nest and nurture the chick once it’s born. In captivity, penguins are “pair bonded” by humans who place them in a room and let nature take over.

Courtship was not working for a pair of young birds named Stanlee (female) and Bernie (male), and the Steinhart staff thought they might be too young to breed. But nature has a way, and both birds eventually got into the swing of things, according to Melton.

“We thought maybe this would not work for this particular pair, then all of a sudden, one day things just started to click for them,” she said.

Stanlee and Burnie produced four chicks: Pogo, Fyn, Nelson and Alice. Fyn can be seen in the exhibit at the academy’s Tusher African Hall. Pogo has since been transferred to the National Aviary in Pennsylvania.

Like many birds, penguins want to mate, so that they can reproduce and pass on their genes. They don’t mate for life, but stay together for a very long time. Occasionally some infidelity, or “shenanigans” may occur in the colony, Melton said.

“When a bird passes away or is moved out, they don’t skip a beat in terms of finding a new partner.”

No two penguins are alike and their individual make up can affect their breeding habits.

“You may have pairs that are satisfied with their nests and then there may be others that want to own all the nests and kick everyone out,’’ Melton said. “But there are lots of different personalities.”

Academy penguins get good care from the six to eight biologists who look after them along with a veterinary care staff. Their experience in pair bonding and other aspects of penguin breeding played a big part in the colony’s reproductive success.

Maintaining an adequate staff is also key to insuring that trained help is always available when needed.

“We rotate people through so that lots of different people have experience,” Melton said. “We like to keep that balance so that we are not caught in a position where we don’t have enough expertise at any given time.”

Part of that training involves academy staff travelling to South Africa every two years where African penguin colonies are threatened by environmental factors such as global warming, depletion of the fish stocks that make up their diet and destruction of their habitat.

Working with the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds, academy biologists, rangers and others rescue eggs abandoned there by the birds and hand raise them before they are released into the wild.

It’s an arrangement that benefits the organization while educating academy biologists on the challenges facing the species.

“We are going to lose our species in the wild if we do not shine our attention on what’s happening in South Africa and Namibia,” Melton said.

“Its great experience and they (our biologists) bring that back to our colony.”

To see how the academy’s colony is doing, visit the live webcam: www.youtube.com/watch?v=KjIdm7eJHuw

Ten chicks have hatched in the academy’s penguin exhibit over the past 14 months ending in January. That might not seem like a lot, but, by comparison, it took a decade to breed the same amount of baby birds previously.

“Our colony is relatively small,” said Brenda Melton, Director of Animal Care and Wellbeing at the Steinhart Aquarium. “While the number of chicks may be common in a larger colony, for us it’s quite a feat.”

Melton serves on the steering committee of an organization of zoos and aquariums which plans the breeding of African penguins, based on maintaining healthy colonies.

Genetic diversity among the birds is crucial if the colonies are to remain healthy and avoid problems based on limited breeding stock. Birds can then remain where they were hatched or be transferred to another facility to bolster other colonies.

In the wild, penguins choose a mate, build a nest and nurture the chick once it’s born. In captivity, penguins are “pair bonded” by humans who place them in a room and let nature take over.

Courtship was not working for a pair of young birds named Stanlee (female) and Bernie (male), and the Steinhart staff thought they might be too young to breed. But nature has a way, and both birds eventually got into the swing of things, according to Melton.

“We thought maybe this would not work for this particular pair, then all of a sudden, one day things just started to click for them,” she said.

Stanlee and Burnie produced four chicks: Pogo, Fyn, Nelson and Alice. Fyn can be seen in the exhibit at the academy’s Tusher African Hall. Pogo has since been transferred to the National Aviary in Pennsylvania.

Like many birds, penguins want to mate, so that they can reproduce and pass on their genes. They don’t mate for life, but stay together for a very long time. Occasionally some infidelity, or “shenanigans” may occur in the colony, Melton said.

“When a bird passes away or is moved out, they don’t skip a beat in terms of finding a new partner.”

No two penguins are alike and their individual make up can affect their breeding habits.

“You may have pairs that are satisfied with their nests and then there may be others that want to own all the nests and kick everyone out,’’ Melton said. “But there are lots of different personalities.”

Academy penguins get good care from the six to eight biologists who look after them along with a veterinary care staff. Their experience in pair bonding and other aspects of penguin breeding played a big part in the colony’s reproductive success.

Maintaining an adequate staff is also key to insuring that trained help is always available when needed.

“We rotate people through so that lots of different people have experience,” Melton said. “We like to keep that balance so that we are not caught in a position where we don’t have enough expertise at any given time.”

Part of that training involves academy staff travelling to South Africa every two years where African penguin colonies are threatened by environmental factors such as global warming, depletion of the fish stocks that make up their diet and destruction of their habitat.

Working with the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds, academy biologists, rangers and others rescue eggs abandoned there by the birds and hand raise them before they are released into the wild.

It’s an arrangement that benefits the organization while educating academy biologists on the challenges facing the species.

“We are going to lose our species in the wild if we do not shine our attention on what’s happening in South Africa and Namibia,” Melton said.

“Its great experience and they (our biologists) bring that back to our colony.”

To see how the academy’s colony is doing, visit the live webcam: www.youtube.com/watch?v=KjIdm7eJHuw

Octopus garden found off California

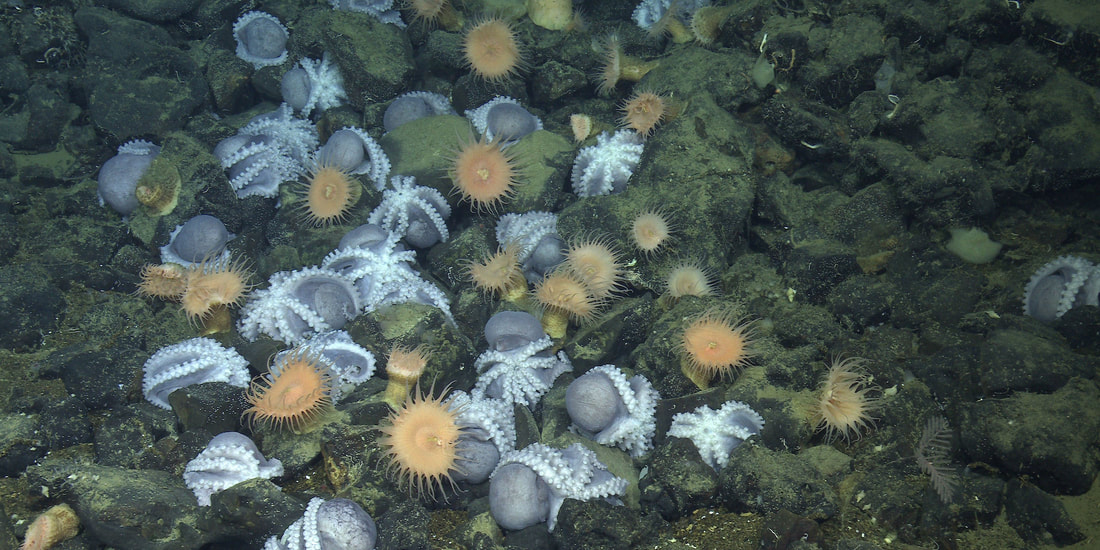

MBARI photo/ Female Pearl octopuses gather on a submerged seamount to brood their young

Sept 1, 2023

To most of us, the term Octopus Garden conjures up a hit song by The Beatles.

But Monterey Bay scientists are letting the world know about a real octopus garden off the California coast.

They say it’s the largest known octopus nursery in the world, where more than 20,000 females brood over eggs that will eventually develop into hatchlings.

About the size of a grapefruit, their species is called Muusoctopus robustus or pearl octopus because the cephalopods resemble a bright string of pearls when nesting in a group.

The octo-moms are attracted to the Davidson Seamount, an extinct underwater volcano located more than 80 miles southwest of Monterey. By clustering around crevices, the females take advantage of warm thermal springs which hasten the babies’ development.

Deep sea octopuses may take as long as four years to brood their young, but these animals incubate their offspring in less than two years. A shorter brood time gives the hatchlings a better chance at life and avoids making them an easy meal for predators, researchers said.

Water temperatures at the nursery site –located at approximately 10,000 feet below the surface- dip to near freezing, but the thermal springs maintain a steady temperature of 51 degrees.

“The deep sea is one of the most challenging environments on Earth, yet animals have evolved clever ways to cope with frigid temperatures, perpetual darkness and extreme pressures,’’said Senior Scientist James Berry, who led the team from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

“Very long brooding periods increase the likelihood that a mother’s eggs won’t survive. By nesting at hydrothermal springs, octopus moms give their offspring a leg up.”

Nurturing a host of eggs is hard work, and females must live off nutrients in their own tissues during the nesting period. Like most cephalopods, they die once the babies hatch. Their bodies then provide food for a variety of nearby scavengers like sharks.

The octopus garden study is outlined in Science Advances and took five years to complete. It was a joint effort including MBARI researchers and teams from the Monterey Bay Marine Sanctuary, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, the University of New Hampshire and the Field Museum of Chicago.

MBARI Photo Female octopuses huddle over warm water vents to brood their eggs

Sharks on drugs may be haunting the oceans

Shark Week: the annual exploration of sharks through nightly documentaries showing the fish attacking humans with abandon.

This year, at least one shark expert is taking the fear factor at one step further. He’s looking for sharks that might be cocaine addicts.

Tom “The Blowfish” Hird has a theory that sharks might be ingesting the drug from the many bales of illegal narcotics tossed overboard as drug dealers are fleeing authorities off the coast of Florida.

And there is plenty to eat, apparently. Two months ago, the U.S. Coast Guard seized 14,000 pounds of cocaine‑worth an estimated $186 million - in the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean. It’s safe to assume that much of the dope that was thrown into the sea was pushed toward shore by waves and currents.

To test his hypothesis, Hird enlisted the aid of University of Florida environmental scientist Tracy Fanara, and filmed his research for a Discovery Channel special: “Cocaine Sharks.”

“The deeper story here is the way that chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and illicit drugs are entering our waterways and what effects they could have on these delicate ocean ecosystems,” he told the website Live Science.

The pair dive off the Florida Keys where they encounter sharks acting in a very unsharklike way. A normally shy Hammerhead shark comes up to the divers, appearing to swim a bit crooked. Another Sandbar shark swims around in circles with nothing in sight.

Finally, Hird and Fanara dump some bales resembling a cocaine shipment into the water. The sharks head straight for the dummy dope, with one shark even taking an entire bale for himself. Presumably for later consumption with his friends.

To recreate drug behavior, the divers create a bait ball containing concentrated fish powder that usually gives predatory fish a rush of dopamine. It hits the water and the sharks appear to party down.

Hird admits that this test is not substantive proof that the sharks are getting high. More research is needed, he said, including tissue samples to see if the sharks are indeed swallowing the illegal drugs.

Far fetched ? But it’s lively television at least.

“Cocaine Sharks” will be shown on the Discovery Channel at 10 p.m. PT on Wednesday, July 26.

This year, at least one shark expert is taking the fear factor at one step further. He’s looking for sharks that might be cocaine addicts.

Tom “The Blowfish” Hird has a theory that sharks might be ingesting the drug from the many bales of illegal narcotics tossed overboard as drug dealers are fleeing authorities off the coast of Florida.

And there is plenty to eat, apparently. Two months ago, the U.S. Coast Guard seized 14,000 pounds of cocaine‑worth an estimated $186 million - in the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean. It’s safe to assume that much of the dope that was thrown into the sea was pushed toward shore by waves and currents.

To test his hypothesis, Hird enlisted the aid of University of Florida environmental scientist Tracy Fanara, and filmed his research for a Discovery Channel special: “Cocaine Sharks.”

“The deeper story here is the way that chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and illicit drugs are entering our waterways and what effects they could have on these delicate ocean ecosystems,” he told the website Live Science.

The pair dive off the Florida Keys where they encounter sharks acting in a very unsharklike way. A normally shy Hammerhead shark comes up to the divers, appearing to swim a bit crooked. Another Sandbar shark swims around in circles with nothing in sight.

Finally, Hird and Fanara dump some bales resembling a cocaine shipment into the water. The sharks head straight for the dummy dope, with one shark even taking an entire bale for himself. Presumably for later consumption with his friends.

To recreate drug behavior, the divers create a bait ball containing concentrated fish powder that usually gives predatory fish a rush of dopamine. It hits the water and the sharks appear to party down.

Hird admits that this test is not substantive proof that the sharks are getting high. More research is needed, he said, including tissue samples to see if the sharks are indeed swallowing the illegal drugs.

Far fetched ? But it’s lively television at least.

“Cocaine Sharks” will be shown on the Discovery Channel at 10 p.m. PT on Wednesday, July 26.

Aged fish keeps swimming on

It was the morning of Nov. 6, 1938 and biologists at the Steinhart Aquarium were awaiting a special delivery.

Soon it arrived, a shipment containing an Australian Lungfish, brought direct from Down Under by Matson Shipping Lines. The fish would join the community of aquatic creatures living in the tanks at The California Academy of Sciences and educating visitors about the aquatic world.

Eighty-two years later, Methuselah is still at Steinhart, making history as possibly the oldest aquarium fish in the world.

At the very least, she has witnessed the evolution of the academy over the years.

Methuselah has outlasted several Steinhart directors, the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, the complete remodeling of the aquarium along with the entire academy building in 2005 and generations of visitors who have gazed into her tank over the years.

That history is not lost on Senior Biologist Ryan Schaeffer, one of the staff members who care for Methuselah.

“She’s been part of a lot of changes, especially the amount of biologists who have worked with her. I find it an honor to be part of that crew,” he said.

“Whether she remembers them I don’t know. I wonder how she compares me with the others.”

No one knows Methuselah’s actual age or sex, but the answers may come from an analysis of her tissue samples sent to Australian scientists, according to Schaeffer.

The Australian lungfish is a very old species that stretches back 300 million years. Known for its brown scales, flat snout and slim body, the animal is thought to be one of the oldest backboned species and is related to fish that left water for land millennia ago.

They are found amid vegetation in slow--moving rivers of southeastern Australia. Having an actual lung-instead of the gills most fish use to breathe underwater- is an advantage when rivers begin to dry up or the water becomes oxygen-poor.

Like her cousins in the wild, Methuselah is slow moving and doesn’t bother the smaller rainbow fish who dart about her in the tank. Though Steinhart has another lungfish tank, Methuselah was given her own space after she seemingly protested being housed with others of her kind by swimming upside down, Schaeffer said. Being the senior fish in the exhibits does have its privileges.

“She was like ‘no roommates for me, I will take my own apartment.”

Lungfish are carnivores, but Methuselah is fed a diet of fish, worms, vegetables and her favorite fruit-figs. Not any figs, mind you, but fresh figs in season.

Many animals can achieve longevity based on a variety of factors (see story below) but droughts, predation and loss of habit from human intervention can be deadly.

Lungfish are sensitive to loss of river water caused by dams and increased sediment from farming. They have been listed as endangered though the species population is stable for now, academy scientists said.

Methuselah gets her name from a biblical character who lived to the ripe old age of 989. She likely won’t reach that age, but it’s certain that the academy’s oldest underwater resident will be around for a while.

“One of the questions we are always asked is how long with it live?” said Steinhart Director Bart Shephard. “Who knows? A fish like that could live for 100 years.”

Soon it arrived, a shipment containing an Australian Lungfish, brought direct from Down Under by Matson Shipping Lines. The fish would join the community of aquatic creatures living in the tanks at The California Academy of Sciences and educating visitors about the aquatic world.

Eighty-two years later, Methuselah is still at Steinhart, making history as possibly the oldest aquarium fish in the world.

At the very least, she has witnessed the evolution of the academy over the years.

Methuselah has outlasted several Steinhart directors, the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, the complete remodeling of the aquarium along with the entire academy building in 2005 and generations of visitors who have gazed into her tank over the years.

That history is not lost on Senior Biologist Ryan Schaeffer, one of the staff members who care for Methuselah.

“She’s been part of a lot of changes, especially the amount of biologists who have worked with her. I find it an honor to be part of that crew,” he said.

“Whether she remembers them I don’t know. I wonder how she compares me with the others.”

No one knows Methuselah’s actual age or sex, but the answers may come from an analysis of her tissue samples sent to Australian scientists, according to Schaeffer.

The Australian lungfish is a very old species that stretches back 300 million years. Known for its brown scales, flat snout and slim body, the animal is thought to be one of the oldest backboned species and is related to fish that left water for land millennia ago.

They are found amid vegetation in slow--moving rivers of southeastern Australia. Having an actual lung-instead of the gills most fish use to breathe underwater- is an advantage when rivers begin to dry up or the water becomes oxygen-poor.

Like her cousins in the wild, Methuselah is slow moving and doesn’t bother the smaller rainbow fish who dart about her in the tank. Though Steinhart has another lungfish tank, Methuselah was given her own space after she seemingly protested being housed with others of her kind by swimming upside down, Schaeffer said. Being the senior fish in the exhibits does have its privileges.

“She was like ‘no roommates for me, I will take my own apartment.”

Lungfish are carnivores, but Methuselah is fed a diet of fish, worms, vegetables and her favorite fruit-figs. Not any figs, mind you, but fresh figs in season.

Many animals can achieve longevity based on a variety of factors (see story below) but droughts, predation and loss of habit from human intervention can be deadly.

Lungfish are sensitive to loss of river water caused by dams and increased sediment from farming. They have been listed as endangered though the species population is stable for now, academy scientists said.

Methuselah gets her name from a biblical character who lived to the ripe old age of 989. She likely won’t reach that age, but it’s certain that the academy’s oldest underwater resident will be around for a while.

“One of the questions we are always asked is how long with it live?” said Steinhart Director Bart Shephard. “Who knows? A fish like that could live for 100 years.”

The hall of fame for animal longevity contains many surprising creatures

An ocean quahog clam can live for 500 years.

Methuselah is not the only member of the animal kingdom to be blessed with a long life.

She’s a relative youngster compared with the Greenland shark that can live to more than 350 years old; a Bowhead whale that may roam the oceans for more than 200 years, and an Aldabra tortoise still going strong at the ripe old age of 175.

Animal longevity results from a variety of natural factors that allow some to age gracefully and others to die relatively young.

An animal’s surrounding environment, size and exposure to predation are key elements.

Cold environments, like the deep Atlantic Ocean, slow the metabolic rate of sharks and marine mammals, allowing them to age at a more leisurely pace. The slow-moving Greenland shark doesn’t expend as much energy as an energy- hungry Great White shark that will live only to age 50.

Being the biggest kid on the block is a real help when you live in a neighborhood full of predators. Asian elephants can live up to 80 years while the little House mouse is lucky to make his fourth birthday before being eaten by a cat or a hawk. Cell biology plays a role in survival as well. Flies die young because their body chemistry cannot replace cells that become damaged.

But an animal’s rate of longevity is mostly determined by human intervention. While an Asian elephant’s body can eliminate dangerous cancer cells in the early stages of the disease, it cannot survive illegal hunting by poachers looking for ivory.

A 500 year old Quahog clam that scientists named “Ming” because it was likely born during the reign of China’s Ming dynasty, has nothing to worry about, provided it does not end up in a bowl of chowder.

Here is a partial list of the animal kingdom’s real senior citizens compiled from National Geographic magazine and the Live Science website:

Quahog clam: 500 years

Greenland shark: 392 years

Bowhead whale: 211 years

American lobster: 100 years

Aldabra tortoise: 175 years

Blue whale: 110 years

Orca (Killer Whale): 90 years.

Asian elephant: 80 years

West Indian manatee: 69 years

American alligator: 77 years

Chimpanzee: 68 years

She’s a relative youngster compared with the Greenland shark that can live to more than 350 years old; a Bowhead whale that may roam the oceans for more than 200 years, and an Aldabra tortoise still going strong at the ripe old age of 175.

Animal longevity results from a variety of natural factors that allow some to age gracefully and others to die relatively young.

An animal’s surrounding environment, size and exposure to predation are key elements.

Cold environments, like the deep Atlantic Ocean, slow the metabolic rate of sharks and marine mammals, allowing them to age at a more leisurely pace. The slow-moving Greenland shark doesn’t expend as much energy as an energy- hungry Great White shark that will live only to age 50.

Being the biggest kid on the block is a real help when you live in a neighborhood full of predators. Asian elephants can live up to 80 years while the little House mouse is lucky to make his fourth birthday before being eaten by a cat or a hawk. Cell biology plays a role in survival as well. Flies die young because their body chemistry cannot replace cells that become damaged.

But an animal’s rate of longevity is mostly determined by human intervention. While an Asian elephant’s body can eliminate dangerous cancer cells in the early stages of the disease, it cannot survive illegal hunting by poachers looking for ivory.

A 500 year old Quahog clam that scientists named “Ming” because it was likely born during the reign of China’s Ming dynasty, has nothing to worry about, provided it does not end up in a bowl of chowder.

Here is a partial list of the animal kingdom’s real senior citizens compiled from National Geographic magazine and the Live Science website:

Quahog clam: 500 years

Greenland shark: 392 years

Bowhead whale: 211 years

American lobster: 100 years

Aldabra tortoise: 175 years

Blue whale: 110 years

Orca (Killer Whale): 90 years.

Asian elephant: 80 years

West Indian manatee: 69 years

American alligator: 77 years

Chimpanzee: 68 years

Penguin chicks are growing up at science academy

photo courtesy of California Academy of Sciences/ Pogo, an African penguin chick was born at the academy last November

Pogo is one lucky African penguin chick.

Unlike her cousins in the wild, she will be fed daily, treated for disease and otherwise attended to by a staff of biologists during her lifetime.

Her home at the California Academy of Sciences is a safe environment, where she will be free from predators and live in an exhibit designed to recreate the outside world.

Pogo was hatched at the academy last November, but was named on Friday, Jan. 20 in time for Penguin Awareness Day. More than 10,000 academy followers took part in a naming contest conducted on social media.

Pogo and another chick were hatched by adults Stanlee (female) and Bernie (male)

The second chick died shortly after birth.

In December, a second pair of eggs were hatched by parents Poppy and Darcy but only one bird survived. The surviving chick was named Oswold Cobblepot by a donor. Fans of Batman know Cobblepot as "The Penguin," one of the Caped Crusader's enemies.

Penguins and other birds have a fairly high mortality rate due to pneumonia, predation and natural selection, said biologist Sparks Perkins.`

“These birds get round the clock care, food, love and everything we can do, but sometimes nature has its way.”

Perkins is one of eight people who care for the penguins and it’s a demanding job.

Along with feeding the birds and cleaning up after them, the team must balance the logistics of moving some penguins into quarantine, replacing others in the exhibit and ensuring that all the birds stay healthy.

Breeding season is a challenge, when males become aggressive and may wound each other during fights. A breeding adult may stop eating and must be force-fed fish so they can feed the baby through regurgitation.

Weak chicks are fed four times a day with a mixture of fish and Pedialyte warmed to 100 degrees and sent through a tube inserted into the chick’s stomach.

It takes dedicated handlers to deal with the constant challenges of raising young birds during this breeding period, according to Perkins.

“You’re dealing with an endangered animal,” he said. “When you have viable pairs and eggs that are super valuable you want to make sure you are doing everything right.”

Pogo and Beta will remain out of public view for the time being as they attend what biologists call “fish school”. They will learn how to eat fish given them by academy staff and grow the waterproof feathers needed to swim on their own.

The penguin enclosure is located at the end of the academy’s African Hall.

Though it’s an artificial environment, the enclosure features lighting that changes throughout the year to replicate the seasons; ultraviolet light promoting natural molting, and a water tank that changes temperature on a seasonal basis.

The penguins’ isolation is also beneficial because they avoid diseases like avian flu which is now forcing many zoos to bring penguins inside.

African penguins are an endangered species which is at risk as their natural environment degrades. Climate change and commercial fishing are depleting the birds’ natural prey of sardines and anchovies, causing them to swim further to find enough to eat.

Oil spills from passing tankers can take a heavy toll on penguin colonies, and humans collecting their guano have eliminated a prime substance needed for nests and hatching, according to the Center for Biological Diversity.

During the past 30 years, the species has declined by 73 percent from 42,500 breeding pairs in 1991 to a little over 10,000 by 2021.

Perkins witnessed the problems first hand late last year when he and fellow biologist Spencer Rennerfelt travelled to South Africa to help rescue birds with the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds. The foundation is a non-profit staffed mostly by volunteers who find abandoned chicks, raise them at a nearby center and eventually release the birds back into the wild.

Early molting, during which penguins cannot swim for prey due to loss of their waterproof feathers, caused many adult penguins to abandon their babies this year, according to Perkins.

When the academy biologists arrived, the center staff was rescuing 120 birds a day. That number had grown to 500 birds daily when Perkins and Rennerfelt left two weeks later.

“It was very intense work,” Perkins said. “We were tubing birds, feeding babies four times a day and cleaning enclosures. It was long days, but it paid off by what we were doing helping these birds.”

And perhaps the future may be brighter for the species. The academy has raised penguins for the Species Survival Plan, in which zoos and aquariums breed the birds to replenish African penguin colonies.

Stanlee and Bernie are an officially recommended breeding pair, so their parenting may have some value in ensuring that the unique species does not disappear.

Unlike her cousins in the wild, she will be fed daily, treated for disease and otherwise attended to by a staff of biologists during her lifetime.

Her home at the California Academy of Sciences is a safe environment, where she will be free from predators and live in an exhibit designed to recreate the outside world.

Pogo was hatched at the academy last November, but was named on Friday, Jan. 20 in time for Penguin Awareness Day. More than 10,000 academy followers took part in a naming contest conducted on social media.

Pogo and another chick were hatched by adults Stanlee (female) and Bernie (male)

The second chick died shortly after birth.

In December, a second pair of eggs were hatched by parents Poppy and Darcy but only one bird survived. The surviving chick was named Oswold Cobblepot by a donor. Fans of Batman know Cobblepot as "The Penguin," one of the Caped Crusader's enemies.

Penguins and other birds have a fairly high mortality rate due to pneumonia, predation and natural selection, said biologist Sparks Perkins.`

“These birds get round the clock care, food, love and everything we can do, but sometimes nature has its way.”

Perkins is one of eight people who care for the penguins and it’s a demanding job.

Along with feeding the birds and cleaning up after them, the team must balance the logistics of moving some penguins into quarantine, replacing others in the exhibit and ensuring that all the birds stay healthy.

Breeding season is a challenge, when males become aggressive and may wound each other during fights. A breeding adult may stop eating and must be force-fed fish so they can feed the baby through regurgitation.

Weak chicks are fed four times a day with a mixture of fish and Pedialyte warmed to 100 degrees and sent through a tube inserted into the chick’s stomach.

It takes dedicated handlers to deal with the constant challenges of raising young birds during this breeding period, according to Perkins.

“You’re dealing with an endangered animal,” he said. “When you have viable pairs and eggs that are super valuable you want to make sure you are doing everything right.”

Pogo and Beta will remain out of public view for the time being as they attend what biologists call “fish school”. They will learn how to eat fish given them by academy staff and grow the waterproof feathers needed to swim on their own.

The penguin enclosure is located at the end of the academy’s African Hall.

Though it’s an artificial environment, the enclosure features lighting that changes throughout the year to replicate the seasons; ultraviolet light promoting natural molting, and a water tank that changes temperature on a seasonal basis.

The penguins’ isolation is also beneficial because they avoid diseases like avian flu which is now forcing many zoos to bring penguins inside.

African penguins are an endangered species which is at risk as their natural environment degrades. Climate change and commercial fishing are depleting the birds’ natural prey of sardines and anchovies, causing them to swim further to find enough to eat.

Oil spills from passing tankers can take a heavy toll on penguin colonies, and humans collecting their guano have eliminated a prime substance needed for nests and hatching, according to the Center for Biological Diversity.

During the past 30 years, the species has declined by 73 percent from 42,500 breeding pairs in 1991 to a little over 10,000 by 2021.

Perkins witnessed the problems first hand late last year when he and fellow biologist Spencer Rennerfelt travelled to South Africa to help rescue birds with the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds. The foundation is a non-profit staffed mostly by volunteers who find abandoned chicks, raise them at a nearby center and eventually release the birds back into the wild.

Early molting, during which penguins cannot swim for prey due to loss of their waterproof feathers, caused many adult penguins to abandon their babies this year, according to Perkins.

When the academy biologists arrived, the center staff was rescuing 120 birds a day. That number had grown to 500 birds daily when Perkins and Rennerfelt left two weeks later.

“It was very intense work,” Perkins said. “We were tubing birds, feeding babies four times a day and cleaning enclosures. It was long days, but it paid off by what we were doing helping these birds.”

And perhaps the future may be brighter for the species. The academy has raised penguins for the Species Survival Plan, in which zoos and aquariums breed the birds to replenish African penguin colonies.

Stanlee and Bernie are an officially recommended breeding pair, so their parenting may have some value in ensuring that the unique species does not disappear.

Experimental sub designer was enthusiastic about undersea exploration

In 2022, I took part in an online lecture offered by Stockton Rush, the founder of Oceangate Expeditions, a company that brought visitors to the wreck of RMS Titanic, the famed oceanliner that sunk on its maiden voyage in 1912. Rush touted his self-designed submersible, Titan, as a state-of-the-art vehicle that could withstand the tremendous pressure of the deep ocean. He was wrong. The ship imploded while on a dive in June 2023, killing Rush and four passengers.

During the talk, Rush did not mention warnings from other submersible operators that the Titan did not meet build standards for safe diving. He dismissed them, saying his critics were attempting to stifle innovation. The following is a feature story based on Rush's optimistic outlook.

Dave Boitano

During the talk, Rush did not mention warnings from other submersible operators that the Titan did not meet build standards for safe diving. He dismissed them, saying his critics were attempting to stifle innovation. The following is a feature story based on Rush's optimistic outlook.

Dave Boitano

It’s not every day that a successful businessman leaves the corporate world for a voyage to the bottom of the sea.

But Stockton Rush did just that, and he could not be happier.

“I wanted to find new life forms. I wanted to be Captain Kirk,” he said. “I wanted to find something new and do something special.”

In his current role, Rush is more akin to Captain Nemo than Kirk; exploring shipwrecks, observing undersea life and leading expeditions into the ocean depths.

And he is willing to take members of the public with him. Provided they can afford it and are willing to serve as a member of the team.

Rush is founder and Chief Executive Officer of Oceangate, a private company dedicated to deep-sea research. The company has two submarines, Cyclops and Titan, the only five-person undersea research vessel of its kind.

Since creating the company, Rush has led dives into the Gulf of Mexico, San Francisco Bay and the nation’s largest undersea canyon near New York state.

But nothing compares with his expedition to the world’s best known shipwreck, the RMS Titanic in August of 2021.

It’s a legendary story. The luxury liner, touted as “unsinkable” by its owners, sank the night of April 14, 1912 after hitting an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean 300 miles southeast of Newfoundland.

Approximately 1,500 of the 2,200 passengers and crew went down with the ship, due to insufficient lifeboat capacity and a disorganized evacuation effort.

As the ship sank, it broke into two pieces. It came to rest more than 12,500 feet below, sinking into the mud and scattering a large field of debris. It rested undiscovered until oceanographer Robert Ballard came upon the wreck in 1985. Since then, more than 250 people have visited the ship, including film director James Cameron who made a blockbuster movie about the ill-fated voyage.

To reach the Titanic, Rush knew he needed a sub that could reach 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) safely. The Titan was created using high tech carbon fiber technology. Its cylindrical shape allows for five people to descend in pressurized comfort with air conditioning similar to systems used on spacecraft. It’s a far cry from the cramped sphere-shaped submersibles that could hold only two people at a time.

In addition to Rush and a designated scientist, each expedition has room for at least three members of the public who become “mission specialists” during the dives. They can be trained to perform a variety of functions, including taking photographs, sub-to-surface communications and operating sonar equipment.

Along with a spirit of adventure, guests need to be well off financially. A Titanic dive costs $250,000 per person. A mission in the Bahamas will set you back $25,000 but a trip in the waters off Everett, Wash.,-the company’s home- is only $5,000, Rush said.

But this is not a tourist outing. All dives are clearly scientific missions often done in concert with universities. Rush hopes the experience will help the mission specialists spread the love of undersea exploration to others.

“The hope with Titanic is to build of cadre of people who are convinced that there are amazing things to see underwater and great research to do,” he said.

It takes more than two hours to reach the Titanic’s resting place. As the sub leaves the sunlit surface, it descends into a black void populated by creatures who use flashing bio luminescence to communicate or seek prey.

Some stare into the sub.

“Sometimes these bizarre creatures would look at you for a while and decide that you are not worth eating and wander off,’’ Rush said.

During its descent, the sub “drops like a stone” until reaching the bottom, where Rush engages the propulsion system and heads to the Titanic. The dive includes views of the ship’s stern, the debris field, and finally the bow section.

Despite the surrounding gloom, the shipwreck is a colorful sight, with bright hues of red, orange and blue caused by bacteria eating rusted metal.

“The thing that really struck me is how beautiful it is,” Rush said. “All the shipwrecks that I have been on are generally grey and covered with silt, and the colors are from anemones, corals and fish. “

But the ship’s allure as the most famous undersea wreck in history has made it a target for those seeking a piece of history.

Divers working for RMS Titanic Inc., the company that holds salvage rights, have brought up more than 5,000 objects from the debris field including shoes, eyeglasses, dinnerware and a 17-ton section of the bow. Much of the loot is on display in the Luxor Hotel in Las Vegas.

Officials of the federal National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration insist the wreck should be declared off limits because the ship may still contain human remains. Scavenging by sea creatures and the deep sea chemistry of the surrounding environment make it unlikely that a human body could last for more than 100 years.

But critics say corpses could remain in sealed areas of the ship, where lack of oxygen would prevent scavenging by worms and other sea life.

Rush said he has not seen human remains when examining the wreck and Cameron agrees.

To protect the wreck, Congress in 1985 passed the Titanic Maritime Memorial Act, but the law was hard to enforce. The United States, Canada and the United Kingdom signed a treaty that toughened the regulations but it needs congressional support.

RMS Titanic salvagers plan to retrieve the Marconi wireless radio that sent the famous S.O.S. the night of the sinking, but a deep-diving robotic probe will have to enter the wreck to get it. A federal judge has approved the dive over NOAA objections.

Oceangate does not salvage objects from the wreck, Rush said. A second expedition planned for this year will be strictly scientific, and he hopes to catalogue the fish and other life living on the ship.

“We’re not going to pick up artifacts, that's not something that I want to do,” he said.

Upcoming expeditions will include a dive to the Great Bahama Bank to study sharks, whales and more shipwrecks. Rush also hopes to journey to the South Pacific to observe ships sunk during the Battle of the Coral Sea in World War II. And all in the spirit of science, Rush said.

“We are doing what I think everybody wants,” he said. “Getting information and ocean awareness.”

But Stockton Rush did just that, and he could not be happier.

“I wanted to find new life forms. I wanted to be Captain Kirk,” he said. “I wanted to find something new and do something special.”

In his current role, Rush is more akin to Captain Nemo than Kirk; exploring shipwrecks, observing undersea life and leading expeditions into the ocean depths.

And he is willing to take members of the public with him. Provided they can afford it and are willing to serve as a member of the team.

Rush is founder and Chief Executive Officer of Oceangate, a private company dedicated to deep-sea research. The company has two submarines, Cyclops and Titan, the only five-person undersea research vessel of its kind.

Since creating the company, Rush has led dives into the Gulf of Mexico, San Francisco Bay and the nation’s largest undersea canyon near New York state.

But nothing compares with his expedition to the world’s best known shipwreck, the RMS Titanic in August of 2021.

It’s a legendary story. The luxury liner, touted as “unsinkable” by its owners, sank the night of April 14, 1912 after hitting an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean 300 miles southeast of Newfoundland.

Approximately 1,500 of the 2,200 passengers and crew went down with the ship, due to insufficient lifeboat capacity and a disorganized evacuation effort.

As the ship sank, it broke into two pieces. It came to rest more than 12,500 feet below, sinking into the mud and scattering a large field of debris. It rested undiscovered until oceanographer Robert Ballard came upon the wreck in 1985. Since then, more than 250 people have visited the ship, including film director James Cameron who made a blockbuster movie about the ill-fated voyage.

To reach the Titanic, Rush knew he needed a sub that could reach 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) safely. The Titan was created using high tech carbon fiber technology. Its cylindrical shape allows for five people to descend in pressurized comfort with air conditioning similar to systems used on spacecraft. It’s a far cry from the cramped sphere-shaped submersibles that could hold only two people at a time.

In addition to Rush and a designated scientist, each expedition has room for at least three members of the public who become “mission specialists” during the dives. They can be trained to perform a variety of functions, including taking photographs, sub-to-surface communications and operating sonar equipment.

Along with a spirit of adventure, guests need to be well off financially. A Titanic dive costs $250,000 per person. A mission in the Bahamas will set you back $25,000 but a trip in the waters off Everett, Wash.,-the company’s home- is only $5,000, Rush said.

But this is not a tourist outing. All dives are clearly scientific missions often done in concert with universities. Rush hopes the experience will help the mission specialists spread the love of undersea exploration to others.

“The hope with Titanic is to build of cadre of people who are convinced that there are amazing things to see underwater and great research to do,” he said.

It takes more than two hours to reach the Titanic’s resting place. As the sub leaves the sunlit surface, it descends into a black void populated by creatures who use flashing bio luminescence to communicate or seek prey.

Some stare into the sub.

“Sometimes these bizarre creatures would look at you for a while and decide that you are not worth eating and wander off,’’ Rush said.

During its descent, the sub “drops like a stone” until reaching the bottom, where Rush engages the propulsion system and heads to the Titanic. The dive includes views of the ship’s stern, the debris field, and finally the bow section.

Despite the surrounding gloom, the shipwreck is a colorful sight, with bright hues of red, orange and blue caused by bacteria eating rusted metal.

“The thing that really struck me is how beautiful it is,” Rush said. “All the shipwrecks that I have been on are generally grey and covered with silt, and the colors are from anemones, corals and fish. “

But the ship’s allure as the most famous undersea wreck in history has made it a target for those seeking a piece of history.

Divers working for RMS Titanic Inc., the company that holds salvage rights, have brought up more than 5,000 objects from the debris field including shoes, eyeglasses, dinnerware and a 17-ton section of the bow. Much of the loot is on display in the Luxor Hotel in Las Vegas.

Officials of the federal National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration insist the wreck should be declared off limits because the ship may still contain human remains. Scavenging by sea creatures and the deep sea chemistry of the surrounding environment make it unlikely that a human body could last for more than 100 years.

But critics say corpses could remain in sealed areas of the ship, where lack of oxygen would prevent scavenging by worms and other sea life.

Rush said he has not seen human remains when examining the wreck and Cameron agrees.

To protect the wreck, Congress in 1985 passed the Titanic Maritime Memorial Act, but the law was hard to enforce. The United States, Canada and the United Kingdom signed a treaty that toughened the regulations but it needs congressional support.

RMS Titanic salvagers plan to retrieve the Marconi wireless radio that sent the famous S.O.S. the night of the sinking, but a deep-diving robotic probe will have to enter the wreck to get it. A federal judge has approved the dive over NOAA objections.

Oceangate does not salvage objects from the wreck, Rush said. A second expedition planned for this year will be strictly scientific, and he hopes to catalogue the fish and other life living on the ship.

“We’re not going to pick up artifacts, that's not something that I want to do,” he said.

Upcoming expeditions will include a dive to the Great Bahama Bank to study sharks, whales and more shipwrecks. Rush also hopes to journey to the South Pacific to observe ships sunk during the Battle of the Coral Sea in World War II. And all in the spirit of science, Rush said.

“We are doing what I think everybody wants,” he said. “Getting information and ocean awareness.”

Sharks plague New England swimmers

Story and photos by Dave Boitano

Tourists scan the ocean at the Cape Cod National Seashore looking for Great White Sharks, (top) warning flags tell swimmers that sharks are present and to stay out of the water, (bottom) and a video at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution shows a shark attacking an underwater drone.(middle)

A cold wind swept across the sands of the Cape Cod National Seashore as a pair of college-enrolled lifeguards kept watch on the waves hitting the beach.

Not the kind of day that would encourage beach goers to take a dip in the water or go Boogieboarding in the surf.

But the crowds were gone for a more sinister reason. The lifeguards' post was flying a red warning flag and a purple banner with the outline of one of the ocean’s top predators: the great white shark.

In what could only be termed a case of life imitating art, great whites have returned to the waters off the Cape, the scene of the hit movie “Jaws”.

In the film, based on the novel by writer Peter Benchley, a marauding shark kills bathers near Martha’s Vineyard, a popular tourist island.

The story became frighteningly real in September 2018 when a 26-year-old man, Arthur Medici, died after he was attacked while boogie boarding off Newcomb Hollow Beach..

Only weeks before, a swimmer was bitten off Truro Beach, but the victim survived by hitting the animal as it attacked his legs.

Medici’s death was the first shark fatality in the area since 1936.

There were no attacks on the Cape this summer because public safety crews took steps to warn and protect bathers.

If a shark was seen feeding nearby, lifeguards would raise the flags and evacuate the water until the animal left. Warning signs urging beach goers to “Be shark smart” were put up at all beaches

Swimmers had to get out of the surf several times this year and an annual charity swim was cancelled due to concerns about shark activity.

Beach goers can report great white sightings by logging onto the Sharktivity app created by the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, a non-profit focused on educating the public about the fierce fish.

The information may be useful but cannot replace scientific methods of measuring shark populations according to Greg Skomal, senior fisheries scientist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries.

“If I put a plane in the air and count 20 sharks over six hours it’s hard to determine if that’s 20 individual sharks or the same four sharks seen five times each,” he said.

The great whites hunt the shallow beach waters in pursuit of their favorite meal, grey seals whose numbers have increased dramatically over the years after the seals became a protected species under the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act. passed in 1972. And given that some estimates place the number of Grey seals on the Cape at 50,000, the sharks will likely continue their summer visits for a long time.

Great whites are most active in New England waters between June and October and can be found in as little as six feet of water while pursuing their prey. During winter Great Whites migrate to warmer waters off the coast of South Carolina and the Gulf of Mexico.

Attacks on humans are rare and are often a case of mistaken identity; the shark assuming that a surfer or swimmer’s splashing contour is that of a seal. But the 2018 attacks convinced tourists and emergency crews to take precautions when sharks are lurking offshore, according to Skomal.

“The chances of being attacked are extremely low, but it doesn’t take many to alarm the general public,” he said.

Since 2009, Skomal and other Department of Marine Fisheries scientists have been conducting research into all aspects of great white behavior. To study the predator’s movements, they have used high tech tagging systems, including acoustic transmitters that register data with strategically-placed buoys when the fish swims by.

Working with engineers at nearby Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Skomal has traced tagged sharks using an autonomous underwater drone that follows the animal as it travels through deep water. A video in the institution’s visitor’s center shows a shark attacking the torpedo-shaped drone only to give up when it becomes obvious that he cannot eat it.

The device itself, complete with huge bite marks, is on display nearby.

That incident took place in clear deep waters off Guadalupe Island in Mexico. Skomal who had tagged the shark, said the animal was not biting because he was irritated at being followed by the device.

“We think it was predatory behavior,” he said.

Skomal and the fisheries department are ending a five-year study to determine the actual number of Great Whites that visit the Cape seasonally. They used a spotter plane to locate the sharks and relay their location to a waiting boat. Skomal and others would then photograph the animals using an underwater camera. By comparing the shark’s individual coloring patterns, the scientists could determine if this animal was a new visitor or had been to the cape before.

This procedure was admittedly time consuming and it will take a few months to analyze all the data. But the study is now more important than ever in light of the 2018 attacks, Skomal said.

“It really did step up the urgency not just with our research but within the public safety community,” he said. “It captured everyone’s attention. "

But perhaps there is a silver lining to the cloud surrounding the shark situation. Some visitors are visiting the seashore in hopes of seeing a great white from a safe distance. The predators should not be hard to find. Just look for the purple flag.

Not the kind of day that would encourage beach goers to take a dip in the water or go Boogieboarding in the surf.

But the crowds were gone for a more sinister reason. The lifeguards' post was flying a red warning flag and a purple banner with the outline of one of the ocean’s top predators: the great white shark.

In what could only be termed a case of life imitating art, great whites have returned to the waters off the Cape, the scene of the hit movie “Jaws”.

In the film, based on the novel by writer Peter Benchley, a marauding shark kills bathers near Martha’s Vineyard, a popular tourist island.

The story became frighteningly real in September 2018 when a 26-year-old man, Arthur Medici, died after he was attacked while boogie boarding off Newcomb Hollow Beach..

Only weeks before, a swimmer was bitten off Truro Beach, but the victim survived by hitting the animal as it attacked his legs.

Medici’s death was the first shark fatality in the area since 1936.

There were no attacks on the Cape this summer because public safety crews took steps to warn and protect bathers.

If a shark was seen feeding nearby, lifeguards would raise the flags and evacuate the water until the animal left. Warning signs urging beach goers to “Be shark smart” were put up at all beaches

Swimmers had to get out of the surf several times this year and an annual charity swim was cancelled due to concerns about shark activity.

Beach goers can report great white sightings by logging onto the Sharktivity app created by the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, a non-profit focused on educating the public about the fierce fish.

The information may be useful but cannot replace scientific methods of measuring shark populations according to Greg Skomal, senior fisheries scientist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries.

“If I put a plane in the air and count 20 sharks over six hours it’s hard to determine if that’s 20 individual sharks or the same four sharks seen five times each,” he said.

The great whites hunt the shallow beach waters in pursuit of their favorite meal, grey seals whose numbers have increased dramatically over the years after the seals became a protected species under the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act. passed in 1972. And given that some estimates place the number of Grey seals on the Cape at 50,000, the sharks will likely continue their summer visits for a long time.

Great whites are most active in New England waters between June and October and can be found in as little as six feet of water while pursuing their prey. During winter Great Whites migrate to warmer waters off the coast of South Carolina and the Gulf of Mexico.

Attacks on humans are rare and are often a case of mistaken identity; the shark assuming that a surfer or swimmer’s splashing contour is that of a seal. But the 2018 attacks convinced tourists and emergency crews to take precautions when sharks are lurking offshore, according to Skomal.

“The chances of being attacked are extremely low, but it doesn’t take many to alarm the general public,” he said.

Since 2009, Skomal and other Department of Marine Fisheries scientists have been conducting research into all aspects of great white behavior. To study the predator’s movements, they have used high tech tagging systems, including acoustic transmitters that register data with strategically-placed buoys when the fish swims by.

Working with engineers at nearby Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Skomal has traced tagged sharks using an autonomous underwater drone that follows the animal as it travels through deep water. A video in the institution’s visitor’s center shows a shark attacking the torpedo-shaped drone only to give up when it becomes obvious that he cannot eat it.

The device itself, complete with huge bite marks, is on display nearby.

That incident took place in clear deep waters off Guadalupe Island in Mexico. Skomal who had tagged the shark, said the animal was not biting because he was irritated at being followed by the device.

“We think it was predatory behavior,” he said.

Skomal and the fisheries department are ending a five-year study to determine the actual number of Great Whites that visit the Cape seasonally. They used a spotter plane to locate the sharks and relay their location to a waiting boat. Skomal and others would then photograph the animals using an underwater camera. By comparing the shark’s individual coloring patterns, the scientists could determine if this animal was a new visitor or had been to the cape before.

This procedure was admittedly time consuming and it will take a few months to analyze all the data. But the study is now more important than ever in light of the 2018 attacks, Skomal said.

“It really did step up the urgency not just with our research but within the public safety community,” he said. “It captured everyone’s attention. "

But perhaps there is a silver lining to the cloud surrounding the shark situation. Some visitors are visiting the seashore in hopes of seeing a great white from a safe distance. The predators should not be hard to find. Just look for the purple flag.